Translation of Sophie Scholl’s Gestapo Interrogation Notes

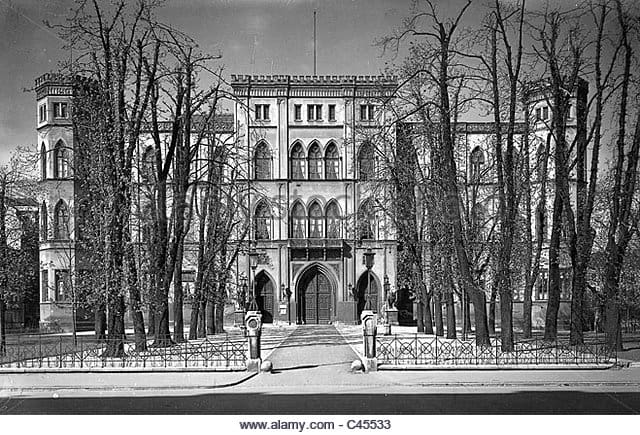

State Secret Police Headquarters, Munich 1943

Briennerstrasse

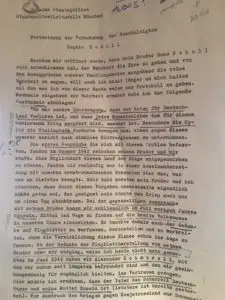

Fortsetzung der Vernehmung der Beschuldigten

Munich, February 20, 1943

Context: Two days earlier, siblings Hans and Sophie Scholl were captured and arrested at the University of Munich after distributing Professor Kurt Huber’s sixth edition of the “German Resistance” leaflets. They were interrogated by Chief Inspector Robert Mohr at the State Secret Police Headquarters on Briennerstrasse.

The below translation of primary archival sources (courtesy of Bundesarchiv Berlin) by Alexandra Lehmann of Sophie Scholl’s Gestapo Interrogation Notes should be read with the understanding that Sophie Scholl had decided to confess to her involvement in the White Rose student resistance. How much of her confession was truthful? The translation below is word for word with no interpretation by the author/translator.

This is a translation from Sophie Scholl’s Gestapo Notes (Page 1-2)

After it has been made clear to me that my brother, HANS SCHOLL, decided to give honor to the truth, and to give the real reasons for our actions, I no longer hold fast to the previous things that I have said.

“It was our conviction that the war was lost for Germany, and that every life that has been sacrificed for this lost war, is for nothing. Especially the fallen at Stalingrad. This meaningless loss of life convinced us even further to do something.

The first conversation about this problem started in the summer of 1942 between my brother and I. At first we were at odds with our growing close circle of acquaintances about what bothered us most. Very quickly my brother and I agreed that we could do nothing about this – and that to be in agreement with them, we would also advocate for a shortening of the war.

Through mutual discussions with my brother we began to discover in July of the same year, methods and ways we could get the mass population to act along our way of thinking. This included the idea of developing leaflets, producing and distributing them, without really understanding what this would mean. Whether or not the idea to produce leaflets came from my brother or I, I do not really know.

Sometime in July 1942, we brought in Alexander Schmorell, with whom we were long befriended and someone who we considered to be like-minded. Here I would like to mention that Schmorell’s father was a German-Russian and his mother was Russian (who has already passed). At the outbreak of the war against Soviet Russia, Schmorell was politically completely uninterested. Only later, after the beginning of the enemy declaration with Russia, did Schmorell begin to become interested. Schmorell loved Russia, although his parents had to flee the country, emigrate to Germany and apply for citizenship here. Schmorell is German. He is absolutely anti-Bolshevik, but he still has feelings for his home country that makes his political beliefs uncertain. After our first conversation with him, he wanted nothing to do with what we were planning. When he did eventually desire to engage with our plans, he did so firstly not because of his overwhelming political beliefs, but because he was enthusiastic to do something.

After many long discussions with this topic between my brother and I, we decided in December 1942 to create a leaflet and to distribute many copies of it.

Schmorell knew of our plans but was not actively involved in them, he was instead first and foremost a bystander and confidant.

…”

An Interpretation of the Entire Transcript

Based on a literal translation of Sophie Scholl’s “confession,” she names Alexander Schmorell as an accomplice in their activities. She later in this confession admits that Schmorell supplied her and her brother, Hans, with a typewriter. She denies the involvement of Willi Graf and Christoph Probst and his wife. She names knowing Fritz Hartnagel (who unwittingly funded the group’s activities), Traute Lafrenz and others – but states adamantly that they did not know about her involvement in the organized protest against the “current state.”